In last week’s blog post, we discussed the potential benefits of re-evaluating where you live and potentially moving every 10 years. Not only does this approach encourage periodic decluttering, it also allows you to “right size” your home to one that works for your current phase of life.

But there’s another important concept to consider when it comes to living arrangements as you grow older: a senior living move that is a “push” versus a move that is a “pull.”

‘Push factors’ driving necessary older adult moves

As people age, certain aspects of their current environment may gradually (or quite suddenly) require them to consider a change in residence.

Among the most common so-called “push factors” necessitating a move is diminishing health or reduced mobility. Another frequent push factor is the loss of a spouse or partner. Whether it’s a large, multi-story home, a poorly designed bathroom, or a maintenance-intensive property, the current home becomes unsafe or burdensome, necessitating a move to a residence that is better-suited to the older adult’s new situation.

When these physical challenges or emotional losses intersect with a deeply held connection to a person’s current home, the tension between comfort and practicality can become a significant stressor. Concurrently, the fear of isolation, the burden of upkeep, or the emotional weight of a major life event (like a serious health issue or losing a partner) can intensify discomfort in one’s current living situation.

Whatever the catalyst for making a move out of necessity rather than choice, older adults may find themselves suddenly seeking an independent living or assisted living retirement community that offers safety and support. But without the emotional or logistical preparation typically involved in a more proactive move, such transitions can sometimes result in “transfer trauma” or relocation stress syndrome (RSS) (as we discussed in last week’s post).

>> Related: Pre-Crisis vs. Post-Crisis Planning: Confronting Life’s Unknowns

‘Pull factors’ attract older adults to new living situations

Conversely, there are also certain reasons older adults may be compelled to make a change to their living arrangements more proactively. These “pull factors” can be especially alluring when aligned with a person’s long-term goals and anticipated needs. It’s this type of thinking that often encourages people to move to a smaller home or even to an independent living retirement community.

Retirement communities with thoughtfully planned independent living residences offer accessible design elements and maintenance-free living that simplify residents’ daily life. Continuing care retirement communities (also called a CCRC or life plan community) also provide residents with a full continuum of care services, should they ever be needed.

Many retirement communities provide social events and activities, as well. Shared common areas like pools, clubhouses, or greenspaces, as well as dining options in some cases, enable residents to connect with one another. These neighborly interactions can counter the loneliness and isolation that can be common for older adults who remain in their current home, particularly for those living alone or with mobility issues.

The economic appeal of downsizing (lower costs, ease of upkeep, and freeing up equity) can also pull people toward embracing change. Yet, the benefits that pull some older adults to proactively move to a smaller home or a retirement community are not only practical but psychological. For many, a smaller, safer home can bring peace of mind and actually help preserve their autonomy.

>> Related: Why Do Many Retirement Community Residents Say, ‘I Wish I’d Moved Sooner’?

Studying later-in-life downsizing

In a 2020 research report entitled When less is more: Downsizing, sense of place, and wellbeing in late life, Dr. Kyrsten Costlow Hill with the University of Alabama’s Research Institute on Aging explored how older adults make decisions to move or stay put when considering downsizing in their later years.

The researchers interviewed 68 older adults across the U.S. who had downsized within the past year, collecting data on push and pull factors influencing those moves, perceived control, sense of place, and outcomes such as move satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. The goal was to understand how motivations for moving shape adjustment after relocation.

The study’s findings revealed that older adults who moved primarily due to push factors like health issues, the loss of their partner, or home maintenance burdens reported lower wellbeing across areas such as purpose in life, environmental mastery, and self-acceptance. These individuals often felt less control over their relocation, making it harder to establish a sense of place in their new homes, which further reduced satisfaction and wellbeing.

In contrast, proactive pull-driven moves motivated by attractions like proximity to family, long-term security, or desirable amenities tended to support more positive outcomes. Such pull effects are grounded in a re-evaluation of what “home” means in later life and whether a smaller place can better align with one’s evolving needs and sense of identity.

The study highlighted relocation controllability and sense of place as key outcome mediators. When older adults feel they have little choice in moving, they may struggle to form emotional attachments to their new residence, undermining their ability to feel “at home.”

This aligns with previous research showing that voluntary moves foster smoother adjustment, while involuntary moves can be disruptive and stressful. It also reinforces what we’ve heard from some retirement community residents over the years: that the people who are less happy in their communities are often the ones who felt forced to be there by their adult kids or other family members.

Overall, Hill’s research also emphasizes the importance of autonomy and proactive planning in downsizing decisions. Furthermore, supports that strengthen a sense of control and help older adults build attachments to their new “place” may mitigate the negative effects of push-driven moves, leading to greater satisfaction and wellbeing after relocation.

>> Related: What’s At the Heart of Older Adults’ Senior Living Apprehensions?

Weaving push and pull into senior living decisions

When framed through the lens of push-pull theory, Hill’s research offers important insights into retirement living decisions. It highlights the emotional complexity of relocation decisions: Downsizing is not simply rational, but involves one’s memories, attachments, and sense of place and continuity.

The push-pull framework helps to clarify this complexity, illustrating that decisions are not made on one axis but along two: what one will leave behind (push) and what one looks forward to gaining (pull) with a move. When push factors such as hazardous living conditions, isolation, or health risks accumulate, they erode the emotional and physical feasibility of “aging in place.” Simultaneously, pull factors like better accessibility, social vibrancy, and financial relief heighten the appeal of a move.

When the cost-benefit balance shifts, older adults (especially those drawing on self-reflection and planning) may choose a proactive senior living transition that better accommodates current and/or future physical limitations while preserving quality of life. In contrast, reactive moves triggered by crises often reflect a build-up of apprehensions and limitations without sufficient opportunity for weighing potential pull advantages. Thus, push moves tend to result in hurried decisions, limited choice of location, and emotional upheaval, especially when made under duress.

>> Related: Memories, Meaning, and Moving On: A Compassionate Guide to Senior Downsizing

Reactive vs. proactive moves put push-pull theory into practice

In contemplating senior living options — whether “aging in place” in one’s current home, downsizing to a smaller home, or moving into an independent living residence — viewing the decision through a push-pull lens provides a more nuanced understanding of a person’s motivations.

Hill’s study shows that senior moves that are thoughtfully considered and planned, with attention to both emotional roots and practical benefits, can be empowering, rather than disruptive. For instance, retirees may opt to begin downsizing before their health declines, selecting a home or retirement community adapted for aging while strengthening social connections and simplifying life.

Such proactive or pull moves can actually enhance older adults’ wellbeing by reimagining the meaning of “home” in a way that balances emotional comfort with functional needs. On the other hand, push or reactive moves taken after a health crisis or sudden loss of support often offer fewer options, reduced control, added stress, and a decline in wellbeing.

All of this underscores the importance of planning for life’s “what ifs” while also respecting a person’s senior living goals. For adult children, care professionals, and those working within the senior living industry, understanding the push-pull dynamics so many people experience can help them better support older adults in planning and exploring viable senior living options, ideally before it becomes a necessity.

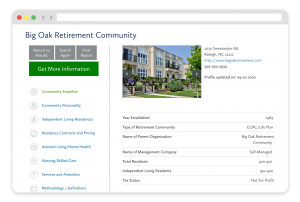

FREE Detailed Profile Reports on CCRCs/Life Plan Communities

Search Communities