Immigration has been a hot topic in the United States lately. Regardless of your opinions on this issue, there’s little dispute that our nation needs some type of immigration reform policy. But what people may not realize is how closely tied another looming nationwide challenge is to the immigration debate. That issue is our country’s impending long-term care crisis.

Shifting demographics

Experts at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) predict that somewhere between 50 and 70 percent of people over the age of 65 will need long-term care services at some point in their life. This could mean they will need help with activities of daily living (ADLs) like eating, dressing, or bathing. Or they may require an even higher level of care like memory care of skilled nursing care.

Another noteworthy statistic has to do with our aging population. In 2030, the last of the baby boomers will reach the age of 65. At that point, more than 1 out of every 5 people in this country will be a senior, and by 2060, that ratio will reach a whopping one in four Americans who will be over 65.

In some states the numbers are even more striking. For example, Maine is currently classified as a “super-aged” state, meaning one-fifth of its population is already age 65 of older. By 2026, more than 15 other states will reach this milestone, and by 2030 an additional dozen-plus will.

And then there are the aging healthcare professionals. Many of our nation’s physicians and nurses are themselves reaching retirement age. In fact, in some rural areas, more than half of the nurses are over age 55. As they reduce their hours or leave the workforce altogether, more and more care facilities are facing staffing shortages.

Add to the equation that birth rates have been trending downward as the aging population grows in many states. On top of this, the nation’s average unemployment rate is at a near-record low of 3.7 percent, so there are fewer and fewer young people who are likely to take on the rigors of a low-paying caregiver job.

So, who is going to take care of all of these seniors? Who is going to help them with ADLs or provide them with the memory care or nursing care they need?

>> Related: Improving the Image of Nursing Care & Assisted Living

Family caregivers

We know that family members act as caregiver to an enormous number of seniors. A 2015 study found that in the prior 12 months, approximately 34.2 million Americans have provided unpaid care to a loved one age 50 or older. Most often, that caregiver role is shouldered by an adult child—commonly, an oldest daughter.

But the downward trend in the birth rate since the 1950s also is coming into play when it comes to the availability of family caregivers. Since the baby boomers who are reaching retirement age now had fewer children than their parents, there are less options for getting help from a loved one. In fact, the so-called “caregiver support ratio,” which was at 7 potential family caregivers to 1 person age 80+ in 2010, will plummet to fewer than 3 to 1 by 2050, according to AARP’s Public Policy Institute.

>> Related: The Challenge of Long-Distance Caregiving

The cost of caregiving

While taking on the role of caregiver to an aging family member is a labor of love, it is also costly to the caregiver as they lose income from lost time at work…not to mention the physical and emotional toll on the caregiver.

For some families, personally caring for an aging loved one simply isn’t an option. Perhaps their job or other family commitments don’t permit them the time required to offer the necessary help. Or maybe they live far away and thus can’t provide the hands-on care that is needed. In these instances, families must hire someone to provide their loved one with care services, either in their own private home or in an assisted living community setting.

But this is a costly proposition too. Medicare doesn’t pay for non-medical assisted living, and only about 10 percent of seniors have a long-term care insurance policy that will cover the costs. That means that most caregiving services must be paid for out of pocket by the senior and/or their family.

The Genworth 2018 Annual Cost of Care Study found that the 2018 median hourly rate for homemaker or home health aide services hired from a home care agency is $21 and $22, respectively. So, for just 20 hours of in-home care (part-time care) per week, the cost can range from around $1,820 to $1,907 each month. That’s on top of other living expenses like food, utilities, and housing.

And this is precisely where the long-term care crisis intersects with the immigration debate.

>> Related: 4 Ways to Pay for Long-Term Care Services

Help from afar

Currently, immigrants (primarily from Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America) account for more than a quarter of home care workers. Despite the growing demand for such paid caregivers, wages remain low for these workers with the average pay rate being around $10.50 an hour (not to be confused with the median rates charged by agencies, as mentioned above). The work can be taxing, mentally and physically, and these caregivers often are living below the poverty level and lack health insurance.

Projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimate that by 2026, as the last of those baby boomers reach retirement age, 1 million more home care workers will be needed in this country. This is on top of the high demand we currently have. That will make caregiving the third fastest-growing occupation in the coming years. That is a lot of low-paying, grueling jobs that will need to be filled.

>> Related: Which is Better: An Independent Caregiver or Home Care Agency?

A supply and demand challenge

Because of this fast-approaching collision of supply and demand for paid caregivers, our nation will need to address this crossroads between immigration and long-term care.

While the job of a care worker is often considered to be “unskilled labor,” the reality is that we don’t have enough Americans who are willing and able to fill these crucial roles. And we are about to experience an influx of seniors who need care. We thus may need to contemplate a way to create a legal route of entry for immigrants who are eager to meet the demand for these paid caregiver jobs.

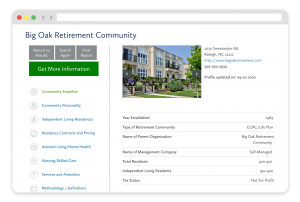

FREE Detailed Profile Reports on CCRCs/Life Plan Communities

Search Communities