The National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago is a well-respected, nonpartisan research organization that studies and analyzes a range of social and economic topics. In 2019, they published their groundbreaking “Forgotten Middle” study, which explored how the number, demographics, health status, and financial resources of middle-income seniors would evolve in the next decade. Recently, they published an update to that study, which had some concerning findings about the future of seniors in the so-called “Forgotten Middle.”

>> Related: Many People Underestimate Their Future Cost of Care

Who are the “Forgotten Middle”?

In the U.S., Medicaid covers the cost of long-term care services for very low-income individuals, including seniors. At the other end of the spectrum, high-income seniors have the financial means to access a wider range of long-term care and senior housing options, paid out of pocket. And then there are the majority of seniors, who fall somewhere in the middle of these two groups.

The term “Forgotten Middle” used in the NORC study refers to those seniors who are middle-income earners with annuitized income and assets from $25,000 to $101,000 in 2018 dollars (this does not include home equity). In other words, these are folks who have too much money to qualify for financial assistance from Medicaid but who likely will have insufficient out-of-pocket/private pay resources to meet their desired or preferred senior housing and care needs down the road.

For this latest update to the “Forgotten Middle” study, NORC researchers analyzed the most current data (2018) from the university of Michigan’s longitudinal Health and Retirement Study (HRS) — an ongoing study that periodically surveys a group of 20,000 Americans over age 50 — to get a better picture of what the future may hold for these middle-income seniors.

>> Related: Becoming an Educated Senior Living Consumer

The challenge of more middle-income seniors

The HRS surveys include questions on a wide range of topics including senior participants’ overall health, health services, economic status, family structure, and more. To create hypotheses about what retirees might look like and experience a decade from now, the NORC team examined the HRS data for individuals who were age 60 and older in 2018 since they will be age 75 or older in 2033. (You can read more about the NORC researchers’ methodologies here.) Some of their findings raise concerns.

- In the coming decade, the number of middle-income seniors will nearly double — reaching 16 million of the adults who will be age 75+ by 2033. These seniors will be increasingly racially and ethnically diverse, including nearly a quarter (22 percent) who are people of color.

- Many of these middle-income seniors will have health needs — including issues like mobility limitations and cognitive impairments — which may make it hard for them to live independently. Additionally, a majority will have three or more chronic health conditions.

- This group of seniors may be more reliant on paid caregivers for several reasons: A majority of them will be unmarried/divorced/widowed in 2033 (oftentimes, a partner is the one who provides unpaid care), and many will not have adult children who live nearby (either in the same home or within a 10 mile radius).

- Without selling their homes, three out of four middle-income seniors (approximately 11.5 million) will have insufficient financial resources to pay for private, in-home assisted living services.

- For a majority of seniors, housing equity constitutes 20 to 40 percent of their financial assets. As is the case with many seniors, folks in this middle-income group will be reluctant to sell their homes, however. Reasons include they hope to “age in place” in their home, their spouse/partner is still living there, it is a “nest egg” to protect for future expenses, or they want to pass it on to their adult children.

- Even with their potential equity from selling their home, more than a third (39 percent, or 6 million) middle-income seniors will not have enough money to pay for assisted living.

You can see a full summary of the latest NORC findings here.

The NORC research highlights some important points about the Baby Boomer generation that is reaching retirement. These seniors have less savings than their parents (the so-called “Silent Generation”), are less likely to have a pension, had fewer children, and are more likely to be “soloagers.” These middle-income seniors thus will present both challenges and opportunities for the senior living industry.

>> Related: The Pain of Paying for Long-Term Care is Real; A CCRC Can Help

Innovative industry solutions

Despite the pandemic’s supply chain and staffing issues, and inflation that has raised the cost of nearly everything, some senior living and care providers have still found creative, lower-cost solutions to meet the growing demand of this middle market demographic.

Some communities have cut down on fancy bells and whistles that can drive up costs and thus prices, opting for more economical options.

For instance, some have eliminated community-provided transportation services for residents, offering ridesharing services that residents pay for out of pocket, as needed, instead. Others have pared down dining services, offering more grab-and-go options and less made-to-order food. To save on food costs, other communities have gone to offering either lunch or dinner, and simpler breakfasts, much like you might get at a hotel’s continental breakfast.

To address staffing costs and shortages, some communities are exploring ways to cross-train employees to work in multiple roles. For example, during a normal shift, a person might work in the dining area for lunch, then move to the front desk or cover set-up/breakdown of a resident entertainment program.

Another cost-saving approach some providers are experimenting with is buying existing multi-family properties with low occupancy to remodel and convert to middle-income senior housing. This is less expensive than new construction, especially given current supply chain issues and construction costs. Other economical senior living and care options include the “continuing care at home” concept and technology solutions.

Put together, such efforts can result in substantial cost-savings for senior living communities’ bottom line and thus enable them to offer lower costs to middle-income seniors while still providing a quality “product.” Although this is a step in the right direction, the senior living industry — and society as a whole — must seek additional solutions to meet the housing and care needs of the growing number of seniors in the “Forgotten Middle.”

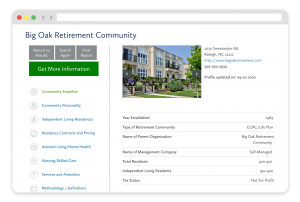

FREE Detailed Profile Reports on CCRCs/Life Plan Communities

Search Communities